MALEVICH AND MATYUSHIN | Two Visionaries of The Russian Avant-Garde of the 20th Century

Posted on April 26, 2017

Alexei Kostroma

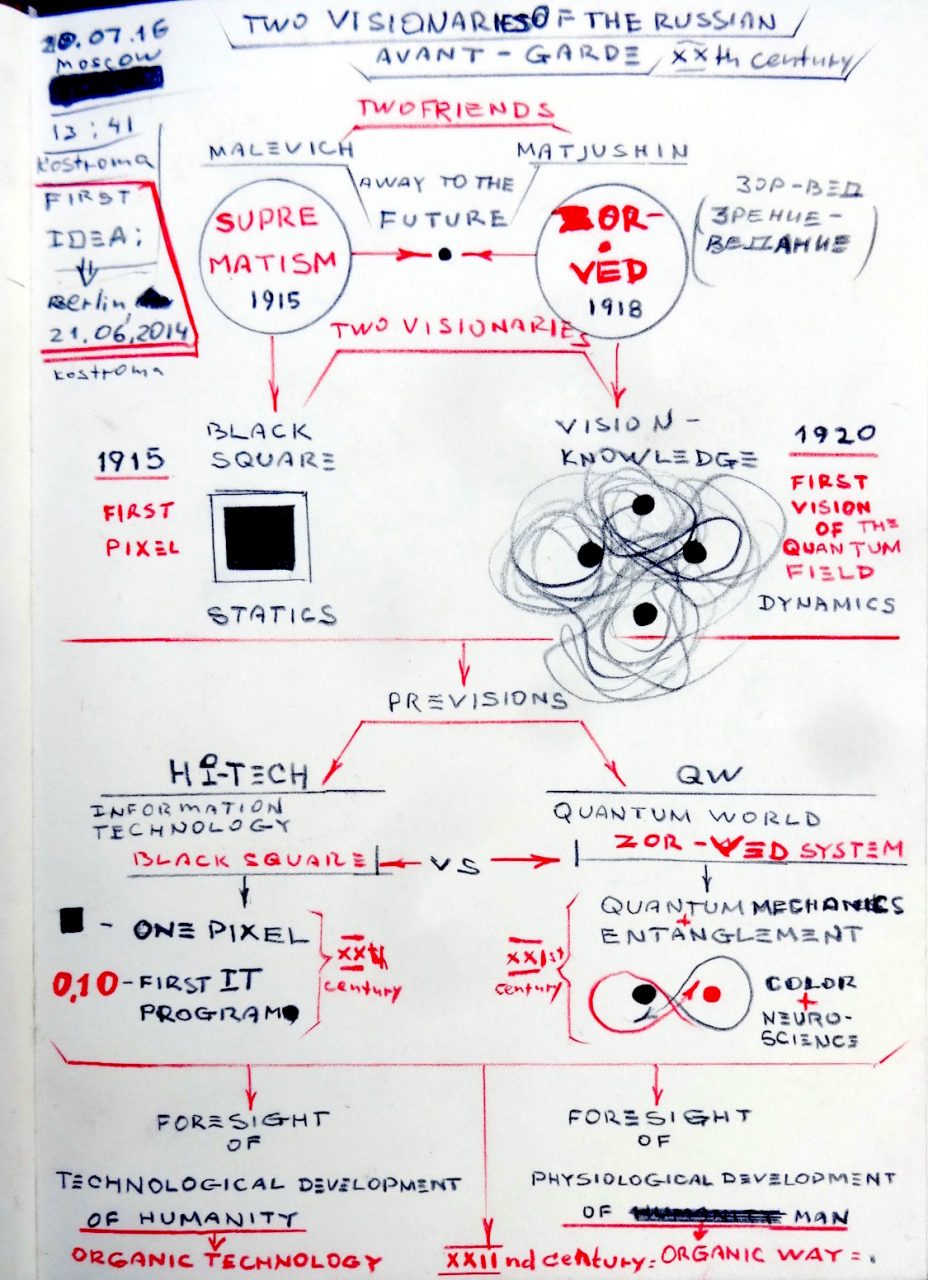

Alexei Kostroma. Malevich and Matyushin. Sketch, 2016

Two artists and thinkers, two friends yet two antipodes, Kazimir Malevich and Mikhail Matyushin counterbalanced one another like plus and minus, each creating his own universe.

Their different character traits meant that the direct and egocentric Malevich had need of Matyushin, the generous and modest intellectual. Observation of the manuscripts of both artists reveals how much the former valued the opinion of the latter. Matyushin, in turn, needed the criticism of a friend who could give harsh judgement and mercilessly speak the truth.

After long decades of oblivion Malevich was elevated to the pedestal of World Art History, but his friend remained for a long time in obscurity.

Until now the role of Matyushin has been greatly underestimated by specialists and researchers of the Russian avant-garde. Why? There are several objective reasons.

The prolific Malevich left behind a fairly extensive creative legacy: paintings, drawings and manuscript material. Unfortunately for Matyushin, after the artist’s death his archive, comprised largely of manuscripts rather than completed works of art, was divided and dispersed among private collections and museums.

It is precisely in the manuscripts that the profundity of Mikhail Matyushin’s lengthy creative endeavour is revealed. His ideas, which went beyond direct statement, were also radical, but in contrast to those of Malevich they were less declaratory and unclear to an unprepared public. Sadly, most of the manuscript material disappeared without a trace. But the scale of the artist’s worldview system is amazing, even in the few fragments of his thinking that we still have today.

Over the years Malevich and Matyushin worked together and discussed new ways of developing the art of the future. As a result, each of them created his unique world outlook.

Kazimir Malevich proclaimed the utilitarian economy of forms in SUPREMATISM.

‘Suprematist form is nothing but the power of the action of utilitarian perfection, the advent of a concrete world’ (K.Malevich, 1923).

In Europe this concept was successfully presented by Malevich in Berlin in 1927. The minimalist concept of Suprematism quickly integrated into the global flow of abstract art in European culture of the 1920s to 1950s.

The functional minimalism of the ‘black square’ has become close to the visual perception of Europeans. Clear, monumental geometric forms impeccably influenced the viewer by their judicious practicality. ‘Quadratisch. Praktisch. Gut‘.

Economy of form proved victorious.

Mikhail Matyushin preached the knowledge of space by means of the ZOR-VED (Vision - Knowledge) system.

‘Comprehension of nature and the world as a single organism through new methods of work, acting in four directions – touch, hearing, sight and thought, in order to create and develop in the artist a new culture and a new organism of perception’ (M. Matyushin, 1922).

Malevich took Matyushin’s tables with him to Berlin, but for unknown reasons they were not exhibited. The presentation of the Zor-Ved system to Berlin’s professional artistic environment was essential for Matyushin, as his only and last opportunity to popularise this idea in Europe. Soviet Russia closed the borders.

Mikhail Matyushin remained in the shadow of his friend Kazimir Malevich for many years.

To date many art historians have written at length about these artists and serious studies of their creativity continue. Even now the magnetic power of the ideas of Malevich-Matyushin compels us to retrace the process over and over again, to rethink the message they sent a century ago.

TWO VISIONARY IDEAS, TWO FUNDAMENTAL PILLARS OF THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE

KAZIMIR MALEVICH

SUPREMATISM AND HIGH TECHNOLOGY

‘The essence of nature remains unchanging in all changing phenomena’ (K. Malevich, Manifesto ‘Suprematist Mirror’, Life of Art, Petrograd/ Saint Petersburg, 1923).

At the exhibition ‘0.10’ (Petrograd/ Saint Petersburg, 1915), Malevich first publicly introduced his concept of ‘Suprematism’, claiming that ‘it changed into the zero of form and went beyond 0 minus 1’. If we consider ‘0’ as the end of life, then ‘minus 1’ is its non-material continuation in the form of information.

Today we are witnessing rapidly developing information and communication technologies. The digital world is becoming a real rather than virtual reality that controls our consciousness, our social behaviour and our entire life. Each action of the global information network is encrypted with the two digits 0 and 1, which are infinitely variable.

The numbers 1 (on) and 0 (off), which were selected to encode data in computer programming, completely control and dictate the activities of modern man.

Malevich completely dispensed with painting and the artist as a ‘prejudice of the past’ and focused on his ‘black square’, compressing the whole world into one symbol.

As the founding father of a prototype of the first pixel, it is unlikely he thought that he could open the door to the virtual reality of the 21st century and become a harbinger of information technology.

It is interesting that on the first page of ‘Suprematism’ (Vitebsk, 15 December 1920), Malevich indicates the developmental path not of art, but of space travel.

Moreover, he foresees the possibility of the emergence of an artificially created technocratic civilisation in the infinite space of the universe :‘the whole living world ready to fly into space and occupy a special place ... ready to live their personal life in a vast elemental scale of planetary systems...’

Introducing the notion of ‘technical organisms’, he anticipates the advent of cutting-edge technology and artificial intelligence so that ‘every Suprematist body will be equipped with reason... will be included in the natural organisation.’

Through the prism of time, Malevich saw the advent of organic nanotechnology, which uses the principles of self-organisation of nature.

MIKHAIL MATYUSHIN

ZOR-VED AND QUANTUM WORLD

‘The most valuable gift for a person and an artist is the knowledge of space’ (M.Matyushin, Manifesto ‘Not Art, Life’, Life of Art, Petrograd/ Saint Petersburg 1923).

Unlike Malevich, who renounced painting, Matyushin delves deeper in search of a new pictorial language.

The focus of attention in the Zor-Ved system was the intensification of mental activity through the perception of nature at 360 degrees. The practice of this so-called ‘expanded looking’ would enable human beings to synchronously observe in all directions simultaneously. The results of this research was sketched and analysed by Matyushin and his students.

In solving specific problems, Mikhail Matyushin preferred collective work on one and the same problem. Each student reproduced his vision of space. All the observers perceived and depicted the same object in different ways. Their brains processed and produced diverse visual information. The object appeared to his students as they conceived it.

Careful observation of nature did not actually result from the object of observed reality, but was a holographic projection of this reality reflected in the human mind.

By studying and analysing the work of the brain, Matyushin dedicated himself to the search for a new spatial dimension (the ‘fourth vertical’), a space created by consciousness that was capable of altering a person’s physical state.

He portrayed his understanding of the materialisation of events occurring in the brain.

The mental creation of reality is revealed to the artist-visionary in the form of the quantum complexity of neural connections that create the space of intersecting spheres.

Laboratory research by Matyushin and his students on the interaction of colour, sound and form led to phenomenal discoveries. In the form of tables as illustrations, the regularity of the change in the shape of an object was demonstrated by a change in colour. The synchronous appearance of simultaneous contrast around the basic colour was also shown as identical to formation of the particle and antiparticle in quantum physics.

Matyushin’s sphere of interest over lapped with the sciences, far removed from fine art. By combining philosophy, anthropology, psychology and neurobiology in the search for answers to his questions, he became a precursor of the development of modern cognitive science. The artist became entirely engrossed in the cognition of space and thereby predicted the existence of an invisible quantum world as infinite as the universe.

©Concept and text by Alexei Kostroma and Ekaterina Kondranina

First idea 23.03.2014. All rights reserved / DACS, London

Berlin, 16.08.2016