DENIS PRASOLOV

...Page is loading...

© Daniela Müller-Brunke

Berlin, Germany

One thing is clear: painting has changed. At the end of the last century

it was already being stated that the standardisation of contemporary

image production under the general term of painting tends to obscure the

differences that now exist both within the medium and in relation to what

has historically been called painting.1 Since then, at least, painting has no

longer been a matter of idealistic utopias; the...

One thing is clear: painting has changed. At the end of the last century

it was already being stated that the standardisation of contemporary

image production under the general term of painting tends to obscure the

differences that now exist both within the medium and in relation to what

has historically been called painting.1 Since then, at least, painting has no

longer been a matter of idealistic utopias; the foreground is now mainly

occupied by painterly questions formulated in an awareness of their social

and institutional framework. Reflection on painting’s own history and

the examination of its relationship to other media, including the so-called

‘new’ ones and the image worlds they generate, are the parameters of

contemporary painterly production. The question is that of the medium’s

self-definition and self-assertion in the network of mutually pervasive and

influential experiences of seeing.

For some time now there has also been an increasing tendency for nonrepresentative

painting to abandon traditional formats or, if it doesn’t, to

question them fundamentally. So it’s all the more surprising that Ivonne

Dippmann, who isn’t exclusively a painter, and who attracted attention

with such things as printed clothing, huge wall pieces, portable metal

sculptures and collages, has now placed a distinct accent on the painted

canvas.

The reason for this is explained in a brief look at her exhibition’s apparently

simple title, which flippantly reduces Mies van der Rohe’s very widely

known oxymoron ‘less is more’ to the trivial statement of the factually

correct More Is More. Behind this is an attitude of wanting to speak less to

baroque exhilaration – although Dippmann obviously has nothing against

opulent colouration – than in the radical cadence of Ad Reinhardt and his

statement ‘Art is art. Everything else is everything else.’ If we remember

that the text which Reinhardt’s quotation originally introduced was written

at a time when in the wake of abstract expressionism the reception of

non-representational painting primarily functioned through the construction

of transcendental truths beyond the works themselves, we can discern

the background against which Dippmann’s works are positioned. A development

was then beginning in which abstraction gained a new dimension

in the dialogue between painting and space. Psychological elements had

had their day.

This art requires an attitude towards it that isn’t only intellectual but

presupposes a particular distance under particular lighting conditions in

specially staged spaces. In More is More the autonomous canvas

undoubtedly dominates the space, but it is entirely anti-contemplative,

that is unsuitable for meditative immersion. Autonomy and inner necessity,

the key competences of classical painting, are abandoned in favour of

strategies that obtain their legitimacy from other images and really existing

circumstances. Multipart paintings, for example, are hung around corners

so that they can’t be perceived as a unity; yet they paradoxically overwrite

the space and redefine it. And there is the addition of a disconcerting

wall painting that recalls a loom and can be classed somewhere between

textile image and metal sculpture.

Here the artist draws directly on conceptions of the work that have to do

with simple, material existence instead of subjectively justified creation. At

the same time she plays with the usual gender-specific ascriptions of the

art world, which likes to assign absurd hierarchies of material and media

to their users. A reflex that Dippmann satirises in numerous, sometimes

wearable textile works.

It is a commonly upheld stereotype that art by women circles around the

body and identity. And it is equally claimed that performance is something

for women, along with everything remotely connected with textiles. ‘Don’t

paint – it’s a men’s world’, said Katharina Grosse, passing on the warnings

of her professors at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf to Siri Hustvedt during

a conversation at the exhibition Queensize.2 She was certainly referring

to her large canvases, and above all the extensive wall paintings, such as

Ivonne Dippmann repeatedly creates.

The wearing of textiles on the body in connection with performance as a

definition of space was in fact introduced into post-war German modernism

by a man – Franz Erhardt Walther. This type of spatialised textile work

has only undergone a few essential changes or amendments since then. Its

main proponent has been the American artist Andrea Zittel, whose blankets

and items of clothing are explicitly designed to be used. Zittel’s model

is clearly the Bauhaus, with its aspiration to bring together the applied and

fine arts. In this sense Dippmann’s textiles are exemplary in the way they

question the traditional boundaries of the genre. They lightly bridge the

gap between academic artistic discourse and handiwork, mediate optical

and haptic space and at the same time address the old question of transferring

three-dimensional space onto a surface.

A further minefield of contemporary art that Dippmann ventures into is

the discussion around colour. Involvement with it generally strikes intellectuals

as dubious. Contours are somehow felt to be clear and distinct,

colour more vague and emotional. Perhaps Dippmann sticks to her guns

for this very reason, continually thinking about the ambivalent relationship

between these two cornerstones of painting. Characteristic here are

leaps between abstraction and figuration – often within a single work.

In contrast to the works of preceding years, which bound colours to the

concrete forms of her preliminary sketch, similarly to colouring-in drawings,

Dippmann’s most recent figures are in fact entirely swathed in colour

fields. They wear abstraction as a costume, as it were. Contrary to the early

small-format images of people and what might be landscapes, the colours

are now superimposed. What functions as an undercolour in one place

can appear elsewhere as a dominant final layer, until the colour fields

ultimately dissolve into loose formations in which one tone flows seamlessly

into another.

For Dippmann, as for McKenzie Wark, abstraction also means ‘to construct

a plane upon which otherwise different and unrelated matters may be

brought into many possible relations’.3 Deleuze and Guattari’s old image

of the rhizome lends itself well to Dippmann’s way of working. Rhizomes,

like the tubers of one-year-old plants, store nutrients, and what is special

about them is that in contrast to other forms of root they are ‘democratic’,

that is they don’t mark a power relation. There is no leading form to which

all other phenotypes work towards. So as soon as a certain size has

been reached they can be divided for propagation at any random point.

Applied to Dippmann’s work it can be said that although not every work

inevitably refers to a similar one, they all ceaselessly establish ‘connections

between semiotic chains, organisations of power, and circumstances relative

to the arts, sciences and social struggles’4 in their own characteristic

way and through the means of art. This also explains the many apparent

contradictions in the artist’s still emergent work. She appears to have no

interest in formally tying herself down. The only recognisable constant is

that her painting and thought processes always inform one another,

coupling in quite different exhibition constellations in pursuit of allembracing

form.

Susanne Prinz

Translation: Michael Turnbull

1 Stefan Germer, ‘Vorsicht, Frisch gestrichen – Thesen zu älteren und

neueren Medien’, in Texte zur Kunst, vol. 31, 1998, pp. 60–65

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LwaVr_OgZE, access: 7.1.2016

3 McKenzie Wark, A Hacker Manifesto, version 4.0, http://subsol.c3.hu/

subsol_2/contributors0/warktext.html, access: 25.1.2016

4 Gilles Deleuze/Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, London 1988

(Text to the show "More is More", Clb Berlin 2016)

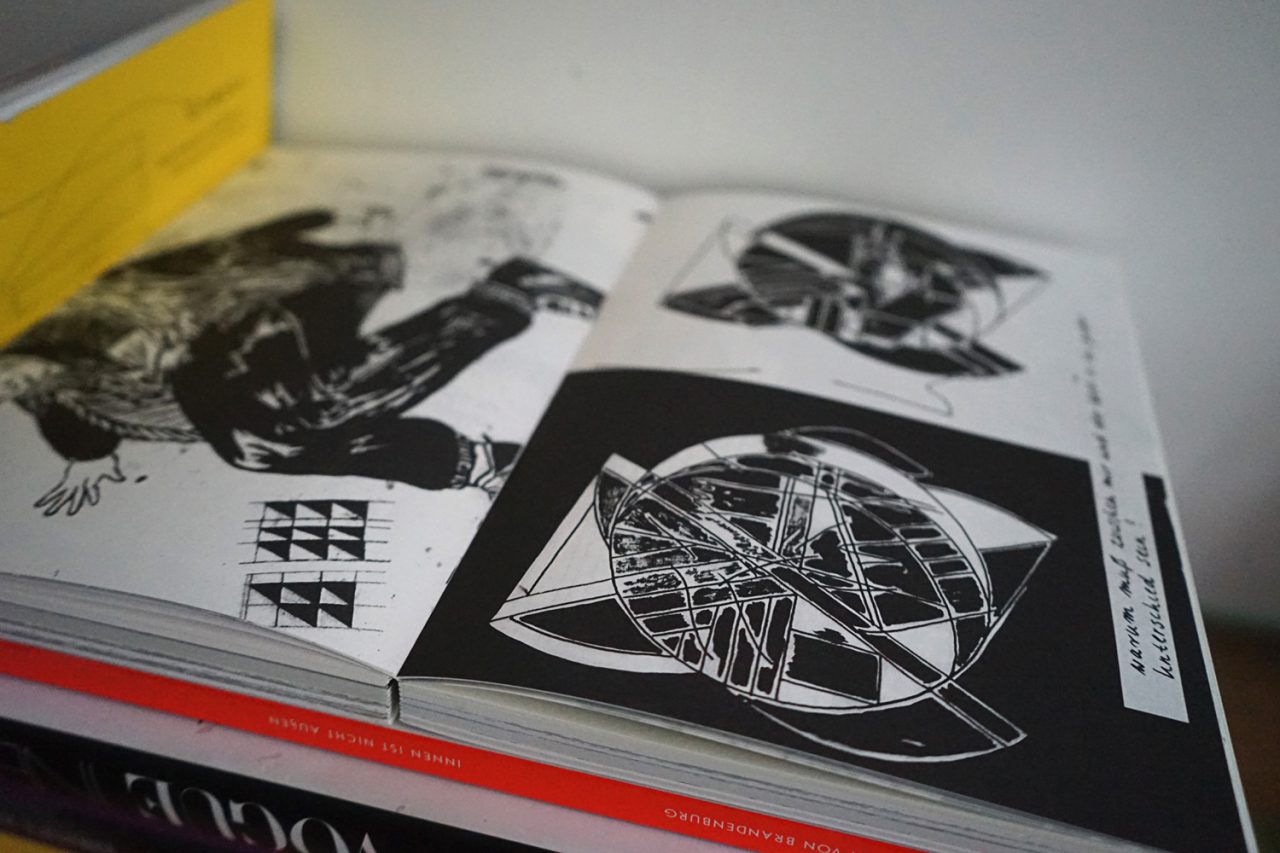

Double Spread Monography "Meine Feindseligkeiten Sind Gerechtfertigt Verteilt" (engl.: My Hostilities Are Distributed In A Justified Way), Revolver Publishing 2013 | © Studio Ivonne Dippmann

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2015 - 021, 022 | 2 x neckline negative, patinated, Ø 20 cm, 2/4 brass objects, production in cooperation with Juliwerk, from an edition of 14 handcrafted unique items, Berlin 2015 © Katrin Greiner

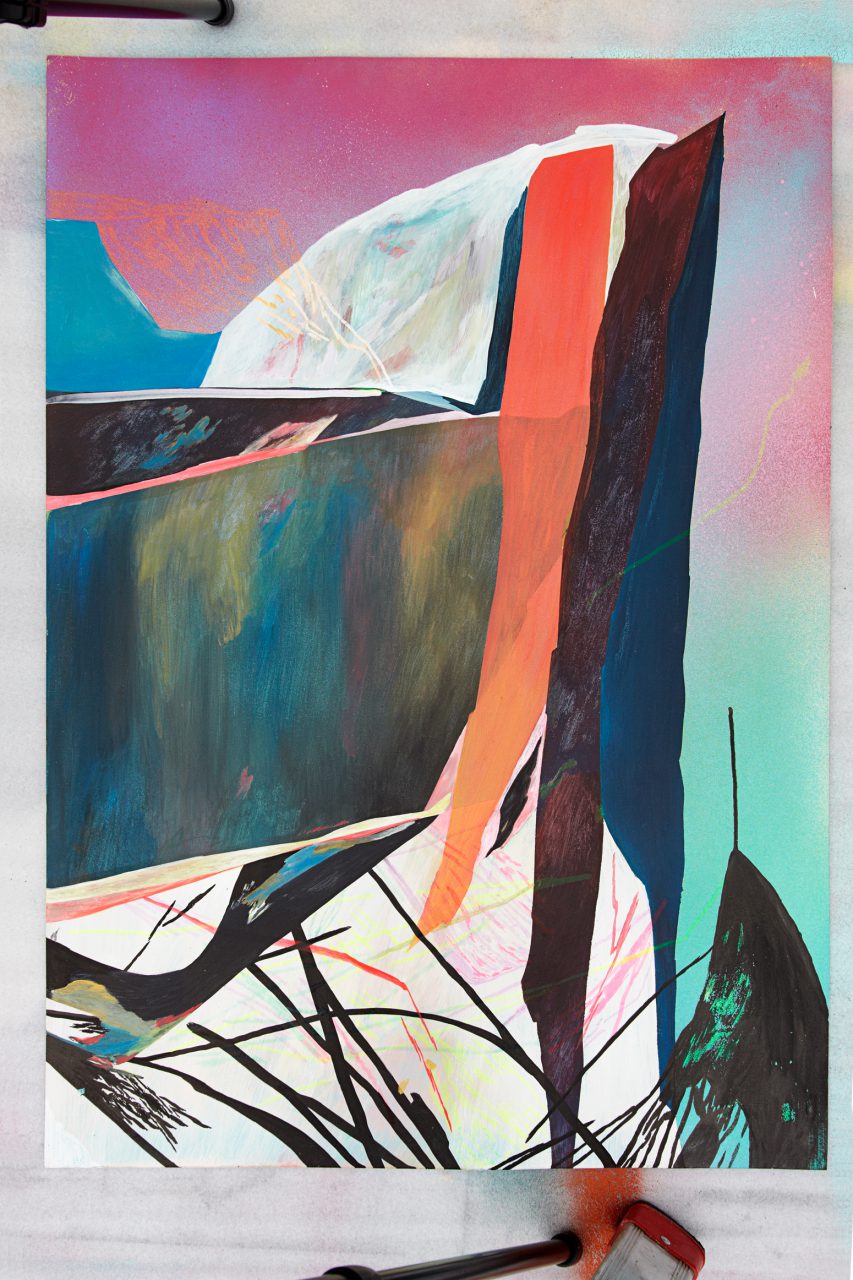

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2015 – 220 until 231/269 | NIKE Air, acrylic, gouache, ink, spraypaint on paper, from a series of 50 drawings , each 100×70 cm, Berlin 2015 | © Studio Ivonne Dippmann

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2015 – 218 | Passed cement in gray/beige, triptych, acrylic, gouache, ink, spraypaint on canvas, 290×420 cm © Michael Belogour, GfjK Baden-Baden 2015

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2016 – 008 bis 015 I WALLS I – VIII, I In winter the trails are not gritted here. II I liked her, that is the better word. III Leave me alone! I’m amused! IV Flowers, which I do not know. V Until the whiskey etched up the ribbons. VI Remainder world. VII Attention! Roof avalanches! VIII In a complete peace of mind in the midst of ruins., from a series of 8 paintings (I – VIII), acrylic, ink, spray paint, gouache on canvas, each 6×140 x 290 cm & 2×200 x 290 cm, total 760×290 cm, Berlin 2016

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2016 – 016 Saal 6, Reihe B, Sitz 5, Acryl, Tusche, Gouache auf Rehgipswand, Gesamt 1500×250 cm, Ivonne Dippmann, Open space area, 6th floor, Mindspace Berlin 2016 © Daniela Müller-Brunke

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2016 – 016 Saal 6, Reihe B, Sitz 5, Acryl, Tusche, Gouache auf Rehgipswand, Gesamt 1500×250 cm, Ivonne Dippmann, Open space area, 6th floor, Mindspace Berlin 2016 © Daniela Müller-Brunke

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2015 – 220 | Paul, acrylic, ink, gouache on wall, total 280×200 cm, Ivonne Dippmann, lobby Mindspace Berlin 2015 © Daniela Müller-Brunke

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2016 – 033 | At the Kaiserkai, acrylic, ink, gouache on wall, 305×532 cm, Hamburg 2016 © Helge Mundt

Ivonne Dippmann WV 2016 – 034 | Out of sight, please continue reading!, acrylic, ink, gouache, spray paint on canvas, steel frame, cable ties black, black rope, rotating, 200×160×35 cm, Berlin 2016

What is it about your studio space that inspires you?

To have everything in one place. To be alone.

What sounds, scents and sights do you encounter while in your studio?

Birds.

What is your favourite material to work with? How has your use of it evolved throughout your practice?

Paper. I always get back to it while trying to work with everything else.

If you weren´t an artist, what would you be doing?

Surfing the world.

What are your favourite places besides your studio?

The ocean and my bed.

2017

THE CAT WAS QUIET UNTIL MORNING, Galerie Rainbow Unicorn, Berlin

EINER FLÜSTERT DEM ANDEREN INS OHR, Galerie Kornhaus, Gmünder Kunstverein

2016

MEHR IST MEHR, CLB Berlin, Deutschland

show all

2016

über[s]malen, xpon-art gallery, Hamburg, Deutschland

T€MPORAR¥ PARADI$€, Rainbow Unicorn, Berlin, Deutschland

RE(A)LATIONS Ivonne Dippmann & Torben Giehler, eingeladen von DAG (Dag Pryzbilla)

show all

2001 - 2009 UNIVERSITÄT DER KÜNSTE, Berlin, Deutschland

2003 - 2004 UNIVERSIDAD PAIS VASCO, Bilbao, Spanien

2004 CALIFORNIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS, San Francisco, USA

show all