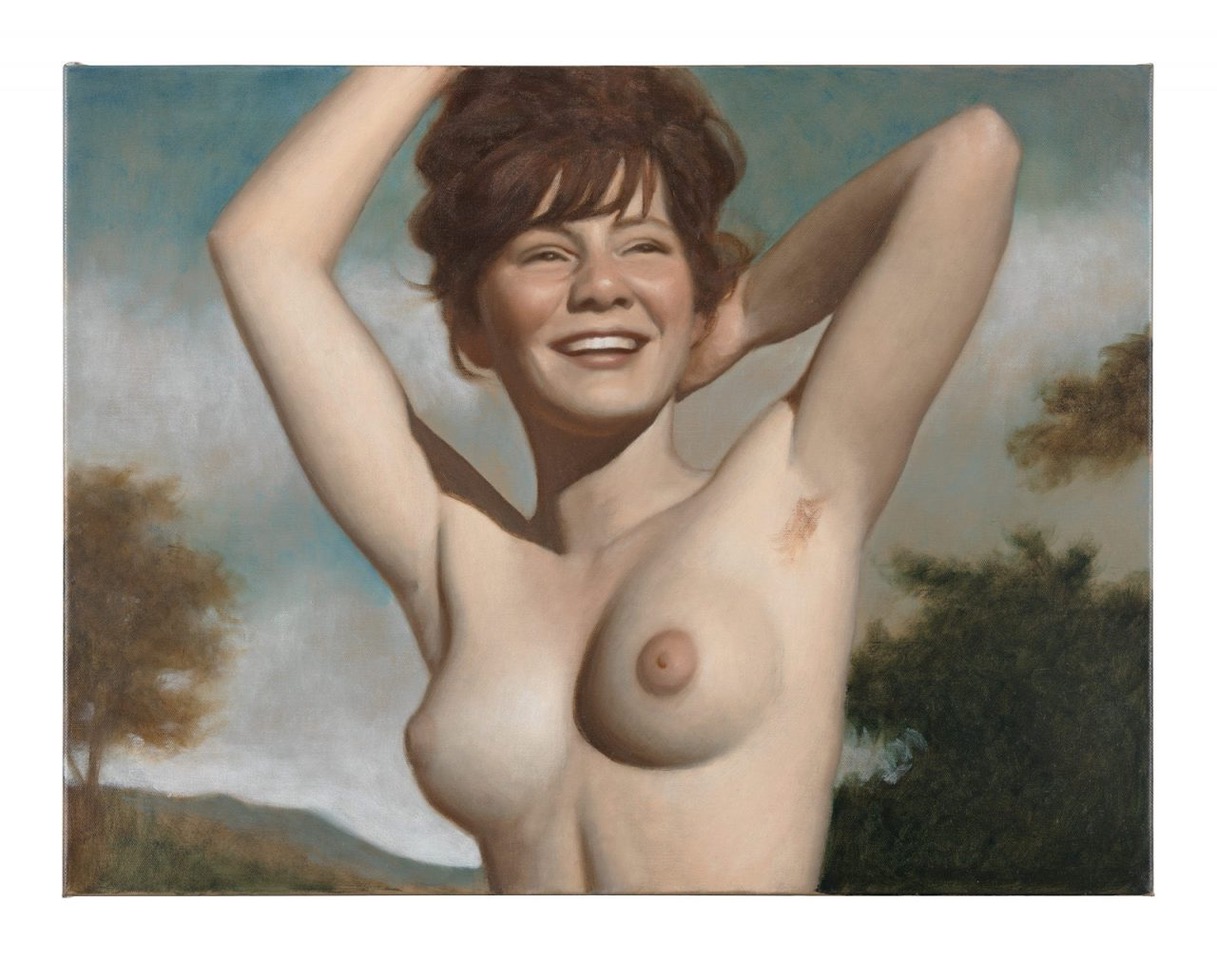

STRANGERS IN PARADISE

MAX RENNEISEN

...Page is loading...

MAX RENNEISEN

MAX RENNEISEN

MAX RENNEISEN

with special participation of

WOLFGANG FLAD

13-14 SEPT 2019 15-19H MOHRENSTRSSE 61, 10117 Berlin

BY REGISTRATION ONLY

CONTACT@WURLITZERCOLLECTION.COM

IN COOPERATION BERLINARTWEEK.COM ARTITIOUS.COM ARTCRATER.COM

Wolfgang Flad, Max Renneisen

The Christian idea of Paradise Lost evokes the belief that humankind once lived in perfect harmony with a peaceful nature that fulfilled all its needs. Civilization and the culture we created following our expulsion from paradise are thereby only surrogates, the corrupt result of our original sin, and must by definition be in strict opposition to nature.

In Greek mythology, the stories of Arcadia and the Golden Age tell of an ideal state of humanity before the development of civilization. In these stories, too, humanity was completely imbedded in the natural environment surrounding it. Wars, crime, and vices were unknown, and humanity’s few necessities of life were fully satisfied by nature.

It is therefore not surprising that the nude in nature is one of the oldest subjects depicted in art. All biblical and mythological themes which could be put in relation to Paradise Lost or to the Golden Age became the material for projections of a world that was purer than the seemingly corrupted present.

Adam and Eve, Venus and Adonis, Diana and Actaeon, Atalanta and Hippomenes, but also Bathsheba and Leda and the Swan – even though all these stories are connected to death and vices, their depictions point to an ideal world in which humankind lives in a close relationship with nature.

Max Renneisen addresses this subject matter at a time when we are not only becoming increasingly aware of how much we have become alienated from nature, but also of how much we have distorted the natural order itself by the manifestations of our need for culture. Renneisen draws from modern images depicting people naked in nature, be it art model books, nudist magazines or historical private photographs, and puts these into landscapes modelled on representations by Nicolas Poussin, Anthonis Van Dyck and Guido Reni as well as Gustave Courbet and Camille Corot. He thereby creates continuity from Baroque imagery to

that of the 20th Century, while at the same time bringing to light the difference between the ideal of nature in the past and the contemporary concept of nature.

First of all, the pieces produced are works of art which, like the works they are modelled on, stand for themselves. They constititute a contemporary interpretation of a classical theme celebrating the representation of the naked body as an end in itself as much as the artistic possibilities inherent in the concept of nature. Yet there are also questions to be asked by the viewer: What do we as human beings expect of nature? Can we really find fulfillment in nature? Is there an ideal relationship with nature? Can we really largely do without our culture, or do we have to accept it as part of our own nature?

In der christlichen Religion lässt die Vorstellung vom Verlorenen Paradies den Menschen glauben, dass er einst in vollkommenem Einklang mit einer friedfertigen und alle Bedürfnisse erfüllenden Natur gelebt hat. Die Zivilisation und die Kultur, die der Mensch sich nach seiner Vertreibung aus dem Paradies aufgebaut hat, sind hiernach bloß ein Surrogat, ein verderbtes Resultat seiner Erbsünde, das grundsätzlich in Opposition zur Natur stehen muss.

In der griechischen Mythologie sind es die Geschichten von Arkadien und vom Goldenen Zeitalter, welche von einem Idealzustand des Menschen vor der Entstehung der Zivilisation künden. Auch in diesen Erzählungen war die Menschheit völlig in ihre natürliche Umwelt eingebettet. Kriege, Verbrechen und Laster waren unbekannt, und die bescheidenen Lebensbedürfnisse des Menschen wurden sämtlich von der Natur befriedigt.

Es verwundert daher wenig, dass der Akt in der Natur einer der ältesten Darstellungsgegenstände der Kunst ist. Alle biblischen und mythologischen Themen, die sich in Verbindung zum Verlorenen Paradies oder zum Goldenen Zeitalter setzen ließen, wurden zu Projektionsflächen für eine edlere Welt, die im Gegensatz zur als verderbt wahrgenommenen Lebensrealität stand. Adam und Eva, Venus und Adonis, Diana und Aktaion, Atalanta und Hippomenes, aber ebenso Bathseba und Leda mit dem Schwan – auch wenn all diese Geschichten mit Tod und Laster verknüpft sind, ihre Darstellungen verweisen auf eine ideale Welt, wo der Mensch in einem engen Verhältnis zur Natur lebt.

Max Renneisen nimmt sich dieser Thematik in einer Zeit an, in welcher sich der Mensch nicht nur zunehmend bewusst wird, wie weit er sich von der Natur entfremdet hat, sondern auch, wie sehr er mit seinem Kulturbedürfnis die natürliche Ordnung selbst ins Wanken gebracht hat. Renneisen greift Vorlagen aus der modernen Bilderwelt auf, die Menschen nackt in der Natur zeigen, seien es Abbildungen aus Künstlermodellbüchern und FKK-Zeitschriften oder historische Privatfotos, und stellt diese in konstruierte Landschaften, die sich an Darstellungen von Nicolas Poussin, Anthonis Van Dyck und Guido Reni, aber auch Gustave Courbet und Camille Corot orientieren. Dadurch wird einerseits eine Kontinuität von der Bilderwelt des Barock bis zu der des 20. Jahrhunderts geschaffen, andererseits aber auch der Unterschied zwischen dem Naturideal der Vergangenheit und dem Naturverständnis des modernen Menschen zu Tage gefördert.

Die entstandenen Arbeiten sind Kunstwerke, die wie ihre Vorbilder zunächst für sich selbst stehen. Sie sind eine zeitgenössische Interpretation eines klassischen Themas, welche die Darstellung des nackten Körpers in der Malerei als Selbstzweck ebenso feiert wie die malerischen Möglichkeiten der Naturkonstruktion. Jedoch drängen sich dem Betrachter auch Fragen auf: Was erwartet der Mensch von der Natur? Kann er tatsächlich in der Natur glücklich werden? Gibt es ein ideales Verhältnis zur Natur? Kann der Mensch tatsächlich weitgehend auf seine Kultur verzichten, oder muss er sie als einen Teil seiner eigenen Natur akzeptieren?

Berlin, September 2019